Sophoclean sense, is achieved as the house lights come up at the end or the session ends or the film credits roll.

The essay 'This is not a game' is a perfect description of how modern technology can involve game players in a false reality that is greater than any addiction to a television soap. It is a kind of drama that engages the participants totally.

Are there any dangers in the merging of reality with fictional drama?

Docu-dramas can lead to a completely false account of factual historical events; rewriting history to the extent that popular belief relies upon the fictionlised version to inform, to the exclusion of all others, including those which may indeed be nearer to the truth.

High level computer gaming seems to lay the players more open to believing in conspiracy theories than would otherwise be the case in more traditional games. Those activities described by McConical in her very carefully developed essay would lend credence to this view.

If a person lying asleep in a bed has a dream, what is more real, the dream or the reality, that they are in a bed, asleep? The dream, of course.

If a person lying asleep in a bed has a dream, what is more real, the dream or the reality, that they are in a bed, asleep? The dream, of course.But dreams are, by definition, not real.

So, something that is unreal (a dream) can appear to have a greater reality than reality (lying in a bed asleep) itself.

Hence ‘The Arts’ are a way using imagination and dreaming whilst awake, of experimenting with alternative futures by invoking the, ‘what if?’ factor.

This is what I found most appealing about the teaching of drama ~ the world with all its complexities and contradictions, was the raw material from which a drama could be forged.

Conjuring, at its best, does the same thing. ‘What if I could destroy something and make it whole again?’ ‘What if I could fly without any visible means?’ Magic of this kind taps into a dream-like world where anything is possible.

Theatre touches upon human experience, places characters together in a context and watches the sparks fly. In the best writing and performing the audience are led to discover something about the human condition that they may not have previously considered or are led into a view that may not have previously been entertained. In great comedy writing they can be led to see the absurdity of life and to laugh at it.

Both conjuring and theatre also benefit from taking place with live interaction between the participants. The members of the audience, to a greater or lesser extent, are aware of one another. Even in a cinema this is the case.

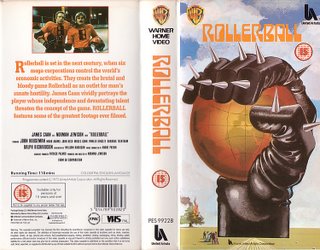

I remember being slightly alarmed as I watched someone’s head being stove in with a viscious spiked glove in a scene from Norman Jewison’s ‘Rollerball’. It was view of the future in which a spectator sport was taken to a height of violence, as yet not attained in our current sporting activities. The spectators in the film were herded like animals behind high wire fences from where they bayed, screamed and yelled like demented, out-of-control, fans at the violent game in front of them. In the darkened cinema the live audience reacted in much the same way as the acting spectators, to this murderous violence. As in the conclusion of ‘Animal Farm’ I looked from screen to live audience and back again, finding it hard to distinguish the difference.

I remember being slightly alarmed as I watched someone’s head being stove in with a viscious spiked glove in a scene from Norman Jewison’s ‘Rollerball’. It was view of the future in which a spectator sport was taken to a height of violence, as yet not attained in our current sporting activities. The spectators in the film were herded like animals behind high wire fences from where they bayed, screamed and yelled like demented, out-of-control, fans at the violent game in front of them. In the darkened cinema the live audience reacted in much the same way as the acting spectators, to this murderous violence. As in the conclusion of ‘Animal Farm’ I looked from screen to live audience and back again, finding it hard to distinguish the difference.The Arts, it seems to me, can be a tool of tremendous power, moving the witnesses to strong reaction. Only the most accomplished creator of the art form can control what that reaction may be.

At the first performances of ‘Waiting for Godot’ audiences booed and left. Was this play an artistic disaster? At the time yes, but now it is acknowledged as a 20th century landmark piece of writing. Perhaps this above all is an argument for an ‘Arts’ education. Something, that sadly, our government policy makers have put quite low down on their list of priorities.

At the first performances of ‘Waiting for Godot’ audiences booed and left. Was this play an artistic disaster? At the time yes, but now it is acknowledged as a 20th century landmark piece of writing. Perhaps this above all is an argument for an ‘Arts’ education. Something, that sadly, our government policy makers have put quite low down on their list of priorities. The Greeks had it as a duty that its citizens attend the great dramatic festivals. Now in Britain, we see nothing but cut-backs in public funding and ever decreasing areas of support for new writers and artists.

The Greeks had it as a duty that its citizens attend the great dramatic festivals. Now in Britain, we see nothing but cut-backs in public funding and ever decreasing areas of support for new writers and artists. The radio version of 'The Lord of the Rings' would not have been commissioned and made had it been submitted today as it would be seen as being too expensive.

The radio version of 'The Lord of the Rings' would not have been commissioned and made had it been submitted today as it would be seen as being too expensive.The BBC once had a sound library that was the envy of the world. Now producers must pay for each loan, whether the track is finally used or not; previously this was simply an available resource. The result is that contributors to programmes end up raiding their own collections to lend, in order to keep the production within budget.

When art is budget-led, wastage is reduced but the quality is also in great danger of suffering.

No comments:

Post a Comment